It is a new year, and high time we had a book review. It has been several months since I linked the names of Jesus Christ and Julius Caesar (here) but, in the meantime, I have come across a much more sensational connection between these two people.

Sensational Theory

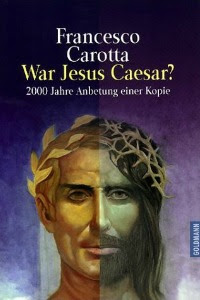

It seems that, for several years now, the left-wing Italian philosopher and ancient history aficionado Francesco Carotta has been promoting his bizarre theory that Jesus was Caesar. (Oddly, in the original Continental versions, the title is phrased as a question: "War Jesus Caesar?" or "Jésus, est-il Divus Julius?")

Signor Carotta's theory seems to be that the Gospel of Saint Mark is a coded retelling of Caesar's life, in which the character of Jesus represents the divine Julius himself. Bizarre? You bet!

His publicity breathlessly announces: "Carotta's new evidence leads to such an overwhelming amount of similarities between the biography of Caesar and the story of Jesus that coincidence can be ruled out." However, so trivial and contrived are these alleged similarities that it is no wonder that no serious reviews have ever appeared, and no recognized authority, whether theologian, historian or philosopher, has yet engaged with Signor Carotta. Here, readers may amuse themselves by deciding for themselves: "Was Jesus Caesar?"

I. Prima Vista.

Signor Carotta's entire theory springs from one unfortunate misconception: the claim that Julius Caesar was known as chrêstos ("worthy"), a word that could have been misconstrued (he argues) as Christos, "Christ". As proof, he first claims that inscriptions of Julius Caesar name him as archiereus megistos, which he interprets as the Greek equivalent of pontifex maximus (Caesar's official religious title as "high priest"). Then, although he does not (cannot?) cite any source that actually calls Julius Caesar "chrêstos" (if Signor Carotta knows of any, why does he not cite them?), he claims that it "looks like a contraction of archiereus megistos", by missing out several letters.

Clearly, this foundation of his theory depends entirely upon Julius Caesar holding the title archiereus megistos, so that it can first be contracted (why?) into chrêstos, and then misconstrued as Christos, "Christ".

Unfortunate Blunder

Unfortunately for Signor Carotta, the overwhelming majority of Caesar's inscriptions name him as archierea kai autokratora (the equivalent of pontifex maximus et imperator) or archierea hypaton (i.e. pontifex maximus, consul) or archierea hypaton kai diktatora (i.e. pontifex maximus, consul et dictator), and only a single inscription is known to name him as archiereus megistos (probably because the megistos element is tautological: archiereus already means pontifex maximus without the addition of the Greek adjective megistos = maximus).

Undeterred, -- indeed, oblivious to his blunder -- Signor Carotta continues with supplementary claims: (1) that Christos resembles pontifex maximus because both can be abbreviated to two letters (i.e. PM, and the Christian Chi-Rho symbol); and (2) that PM looks a little like the Chi-Rho if you invert the letters! Frankly, this sounds a little desperate.

His conclusion, that Caesar's statues "not only looked like a pietà, but the inscription on the base also evoked the Christ", is patently ridiculous: none of the statues survive, so it is only Signor Carotta's opinion that they would have resembled a Renaissance pietà (don't you require a Virgin Mary to make a pietà, in any case?), and none of the inscriptions (some two dozen are known, I believe) "evoke the Christ". Nevertheless, this is Sig. Carotta's springboard "to place Caesar's history and the Gospel (sic, presumably Mark's Gospel) side by side and see if further resemblances (sic) occur".

II. Vitae Parallelae

Signor Carotta claims that "new ground is being broken". Readers can make up their own minds, as I list each of Sig. Carotta's astonishing (astonishingly trivial) similarities.

- Both Caesar and Jesus begin their careers in northern countries beginning with G: Gallia and Galilee.

- Both have to cross a fateful river: the Rubicon and the Jordan.

- Both meet a patron/rival: Pompey and John the Baptist, and their first followers: Antony and Curio, and Peter and Andrew.

- Both are continually on the move, finally arriving at a capital city: Rome and Jerusalem.

- Both at first triumph, but then undergo their passion.

- Both have a special relationship with a woman: Cleopatra and Mary Magdalene.

- Both have encounters at night with "N of B": Caesar with Nicomedes of Bithynia, Jesus with Nicodemus of Bethany.

- Both run afoul of the authorities: Caesar with the Senate, Jesus with the Sanhedrin.

- Both are contentious characters, but show praiseworthy clemency as well.

- Both have a traitor: Brutus and Judas, or Brutus and Barabbas, or Lepidus and Pilate. (Carotta can't quite decide on this one.)

- Both have famous sayings: Caesar's famous "Veni, vidi, vici", Jesus' "I came, washed and saw" (according to Carotta).

- Both are accused of making themselves kings: King of the Romans and King of the Jews.

- Both get killed: Caesar is stabbed with daggers, Jesus is stabbed in his side.

- Both hang on crosses. (Yes, Carotta has an astonishing theory on this.)

It's probably worth just giving a flavor of Carotta's standard of scholarship here: (1) he claims that Pompey's head was presented to Caesar in a bowl (as far as I can see, no ancient source specifies a bowl), "exactly what the Gospels tell us happened to John the Baptist"; (2) he tries to equate Caesar's Lepidus with Pontius Pilate by "syllabic metathesis" so that the name Lepidus mysteriously becomes Pilatus; (3) he claims that both Barabbas and Judas are equivalent to the traitor Decimus Iunius Brutus ("et tu, Brute"), without realising that he has the wrong Brutus; (4) he claims that Jerusalem is code for Rome, because "the other variant of the name (H)ierosolyma, even contains the letters of Roma in sequence: (H)ieROsolyMA"!

III. Crux.

Carotta claims that "We have shown some similarities and parallels between Caesar and Jesus". That's true, though they are all trivial (e.g. both crossed a river) and many are mistaken (e.g. a supposed parallel between Marius and Lazarus as an "uncle" figure). Carotta is so unaware of the fragility of his theory that he sees only one stumbling-block: "Caesar was stabbed and Jesus crucified".

Nevertheless, he claims that a "structural correspondence is plain to see" in the sequence: conspiracy, capture, trial, crucifixion, burial, resurrection. And in order to make this sequence fit both men, he claims that Jesus was actually killed during his capture, and that both he and Caesar were paraded on a cross after their death. This kind of nonsense is surely easy meat for theologians. But let's have a go from the historical perspective.

Jesus' Funeral Pyre

Carotta reinterprets the entire crucifixion as "the erection of a funeral pyre and the ritual deposit of gifts for the dead". Amongst his hotch-potch of evidence, he suggests that the biblical "myrrh" is a linguistic mistake for "(funeral) pyre", and the sour wine is a misinterpretation of the "quickly assembled stakes" (of the funeral pyre? Carotta does not explain this point). He clearly has Plutarch's description of Caesar's funeral pyre in mind, rather than an honest attempt to interpret the Gospel accounts. "It is easy to detect that the passage from Mark is an abridgement of Caesar's funeral". Yes, it's easy when you completely and totally misinterpret it! "No word has been taken away or added", he claims. No, not much! Just a complete rewriting of the Gospel account to fit the story of Caesar's funeral!

Golgotha ("the place of the skull") is equated with the Capitol at Rome, because "the Romans derived Capitolium from caput", the Latin for head. He claims that Mark calls the place Kraniou Topos, which can be altered, "Capi > Kraniou; tolium > Topos", to read Capitolium. (But Mark explains that the place was called Golgotha, so shouldn't Carotta be employing his ingenuity to find some parallel between Golgotha and Capitolium?)

Christ's Tropaeum

Carotta describes Caesar's funeral procession, as a parallel to the Passion of Christ, concentrating on the wax figure of the dead dictator "dressed in his triumphal robes". (Appian, BC 2.147 refers to a wax effigy on which the 23 wounds could be seen, but Suetonius, Div. Jul. 84, mentions only the funerary couch "and, at its head, a tropaeum with the clothing in which he had been killed".) Carotta combines the two descriptions, claiming that the effigy must have been attached to a cross "not only because on a tropaeum the arms could only be fastened like that [but Appian doesn't say that the effigy was on the tropaeum] but because somebody who falls down dead stretches out his arms and because Caesar's body had been seen like that when three servants carried him home with the arms hanging out of the litter on both sides" (the latter is apparently a reference to FGrH 26.97, which I have not seen).

However, if (as Carotta claims) the wax effigy required a wooden core ("they were actually wooden figures with a wax outer-layer"), surely it could adopt any position? Carotta again links the effigy with the tropaeum (two separate items in the story) when he claims that "the most functional and direct way to fasten such a wooden figure coated with wax to a tropaeum would involve nails through the hands" -- of course, this is patently false: there are all sorts of ways to fix a wooden mannequin to a supporting structure, if you decide to do so.

Carotta appeals to the late antique "atypical and unnatural representation of Christ standing on the cross" as proof that such artworks were depicting "the expositio of a stabbed one lying on the floor who was only erected that all could see him". (The reason surely has more to do with artistic limitations in late antiquity.)

IV. Words And Wonders

When Carotta claims that "we determined that Jesus was not crucified, and that a cross had indeed played the main role ... during the cremation of Caesar", he has deluded himself on both counts. There is much more in similar vein.

Caesar's siege of the Pompeians in Corfinium is supposed to be encoded as Jesus' exorcism of the demon called Legion: the giveaway, besides the obvious mention of a Roman "legion" (!), is the fact that both men crossed over: Caesar crossed the Rubicon; Jesus crossed the Sea of Galilee. Jesus walking on water is Caesar crossing from Brundisium. A servant-less Pompey, obliged to take off his own shoes, is John the Baptist claiming to be unworthy of loosening Christ's sandals. Caesar's famous saying, Alea iacta est! ("The die is cast") is paralleled by the Galilee fishermen "casting" their nets. (Yes, Carotta really does employ such facile arguments.) Caesar's visit to Zela is encoded as Jesus visiting Siloam, because "Zela > Siloah is almost the exact same pronunciation"!

It is rather depressing that Carotta is satisfied with such threadbare evidence: "Our question as to whether or not the Gospel is based on an original Caesar source has been answered positively by successfully verifying our suppositions." Clearly, Carotta is no historian.

Finally, if you have managed to read this far, you will be amused to learn that the "fact" that Julius Caesar was historical, but that some scholars dispute the historicity of Jesus, proves that they were one and the same man.

"It must be recognized that the two figures are complementary and that it is only when they are combined that they provide the complete person of a God incarnate", writes Carotta. "Caesar is a historical figure who as a god has vanished without leaving a trace. Jesus, on the other hand, is a god whose historical figure cannot be found."

And all of this nonsense because Caesar was chrêstos. (Or was he?)

Now read the continuing saga: The Carotta Code Cracked | The Parrot Replies | Three strikes, and Carotta is out!

It has been a while since the Antonine Wall was in the news.

It has been a while since the Antonine Wall was in the news.

The latest book to land on my imperial desk is

The latest book to land on my imperial desk is  It seems that the inscription, proclaiming the wisdom of the third century BC philosopher Epicurus, occupied an entire wall of a stoa, or collonaded gallery, perhaps 100m long, which Diogenes had built in the city agora at Oinoanda (Turkey). When the city fell into disrepair, the stoa must have been gradually dismantled and the individual blocks dispersed for reuse across the site, some of them in an emergency defensive wall.

It seems that the inscription, proclaiming the wisdom of the third century BC philosopher Epicurus, occupied an entire wall of a stoa, or collonaded gallery, perhaps 100m long, which Diogenes had built in the city agora at Oinoanda (Turkey). When the city fell into disrepair, the stoa must have been gradually dismantled and the individual blocks dispersed for reuse across the site, some of them in an emergency defensive wall.