I recently came across a book entitled Warfare in the Ancient World by Brian Todd Carey. According to the jacket blurb, Professor Carey is a history lecturer in the American Public University System and vice-president of the Rocky Mountain World History Association. He tells us that the book is intended to accompany his undergraduate course at the American Military University: as he puts it, "unable to find a suitable text, I decided to write my own".

How peculiar. Isn't it school children who require text books? Shouldn't undergraduates be encouraged to read widely? "A little learning ...", as Alexander Pope said. Unfortunately, not even the author seems to have read widely. There are, on average, three end-notes per page (429 notes in all, spread over 149 pages). Something like 10% refer to primary sources: Thucydides, Polybius, Caesar - the actual descriptions of events surviving from antiquity. The rest borrow extensively from a core of modern American popular works: Arther Ferrill's The Origins of War: from the stone age to Alexander the Great; Richard Gabriel & Karen Metz's From Sumer to Rome: The military capabilities of ancient armies; Richard Gabriel & Donald Boose, Jr.'s The Great Battles of Antiquity: a strategic and tactical guide to great battles that shaped the development of war (phew!). He has consulted a similarly small cadre of modern British works, too: Warfare in the Ancient World, edited by General Sir John Hackett; John Warry's Warfare in the Classical World; and (of course) Peter Connolly's Greece and Rome at War.

But (and herein lies the problem) Professor Carey appears not only to have consulted, but to have borrowed heavily, while excluding more specialist works. How, for example, can anyone discuss Gaugamela, the great set-piece battle at the centre of Oliver Stone's recent movie, without referring to Eric Marsden's classic 1964 monograph, The Campaign of Gaugamela?

Academic disciplines like archaeology and ancient history are built on the study of the primary sources: the actual remains, supplemented by a reading of contemporary or near-contemporary textual accounts. For ancient warfare, we think of works like Victor Hanson's The Western Way of War, where the index of ancient citations runs to 11 pages; or Adrian Goldsworthy's The Roman army at War and Hugh Elton's Warfare in Roman Europe, AD 350-425, each based on the respective author's PhD research. To give Professor Carey his due, these works certainly appear in his bibliography, but I wonder whether he has read them.

For example, in the chapter entitled "The Roman Empire at War", we are informed that "the role of Roman cavalry on the battlefield increased because of prolonged contacts with cavalry-based tactical systems in the east" (p. 123). What does this mean? That the emperor Augustus suddenly discovered how useful cavalry could be? Isn't Professor Carey aware, for example, of the frequent cavalry skirmishes during Caesar's African war of 48-46 BC? Or does he mean to imply that the characteristic infantry legions were supplanted by the forerunners of the medieval knight? Elton, for one, has estimated that "at Strasbourg in 357 [the future emperor] Julian had 10,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry". Very similar numbers are found in Arrian's array of AD 132, in his plan to repulse an invasion of the Alans. So, where's the "increased role"?

Also, shouldn't we mistrust any military historian who cannot get the names of famous Roman generals right? It was P. Quinctilius Varus (not Quintilius) who lost three legions in the Teutoburger forest in AD 9, and T. Quinctius Flamininus (not Flaminius) who defeated Philip V of Macedon at Cynoscephalae in 197 BC. And "Scipio the Younger" (younger than whom?) is usually known as Scipio Africanus, and sometimes even Scipio Africanus the Elder!

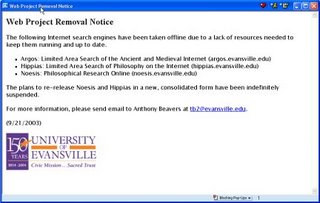

It seems to me that Professor Carey has done his undergraduates a disservice. He has attempted to distill the contents of a few books which are already themselves distilled. In this digital age, it is surely more appropriate to post an annotated reading list as a web site, perhaps with a discussion forum to stimulate some intellectual activity. Then, indeed, Professor Carey's undergraduates can enjoy more than the shallow sip he has offered them.